All characters appearing in this work are fictitious. Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, entities, events and organisations is coincidental.

Fiona Murphy and Eva van Roekel Cordiviola with ChatGPT

I

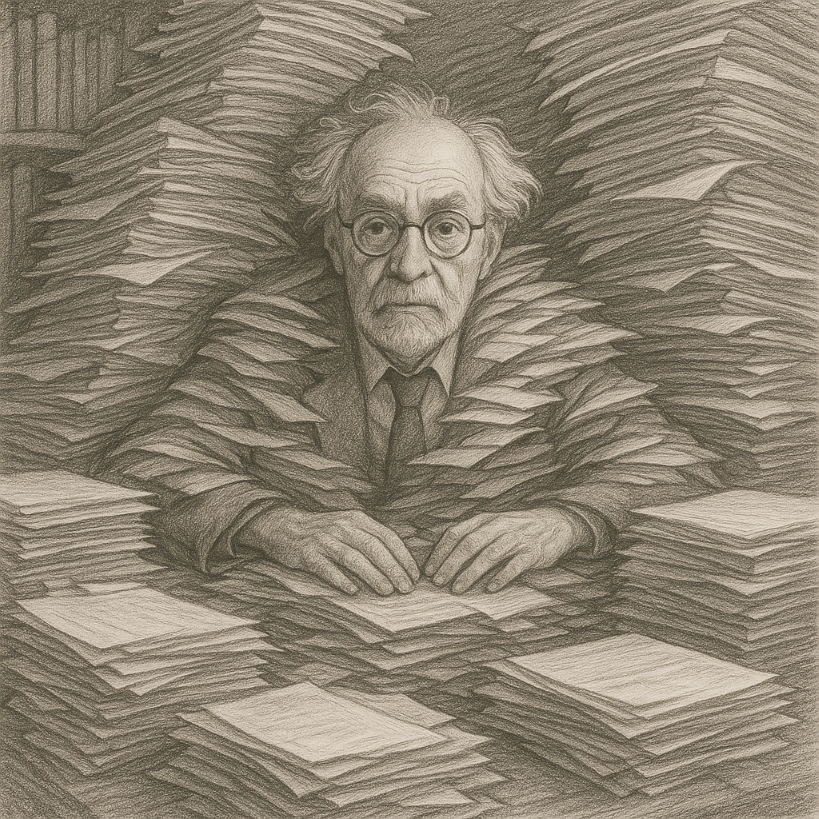

Professor Karel Mulder sat at his desk, wreathed in the noble decay of academia—a kingdom of paper that had long since declared independence from any attempts at order. Journals leaned precariously, manuscripts slumped in resignation, and lecture notes, bearing the faded ink of forgotten brilliance, formed geological layers of intellectual toil. His office smelled of old books, stale coffee, and the quiet despair of peer review.

It was, in short, perfect.

For Karel was a man of paper. He did not trust it, mind you—that would be naïve. He believed in it, in the way others believe in saints or the slow majesty of trains. Paper, he said, was “the last incorruptible medium.” You could mark it, tear it, even burn it—but it never asked to be updated. In an age of PDFs and platforms, Karel remained loyal to ink. His office was a paper mausoleum—stacks leaning like arthritic trees, post-its fading like colonial flags, a chalkboard crowded with esoteric equations underlined twice, as if that lent them more truth.

And the equation—ah, yes. That was his masterpiece. His madness. His gospel.

God ≈ (Fine‑Tuning × Belief) ÷ Entropy

He had found it in a dream, or a journal article, or a Tucker Carlson interview—sources blurred at that altitude. What mattered was that it felt true. The numbers, he insisted, lined up like apostles. He had devoted three years, four ruined conferences, and one increasingly silent marriage to perfecting the maths of divinity.

“Einstein sought elegance,” he would say, gesturing at the formula with the kind of reverence usually reserved for relics. “I seek evidence. In ratios. In resonance.”

His students watched him with the tender bewilderment reserved for gifted eccentrics. They put his quotes on bluesky. They footnoted his paradoxes. Some came to listen; others came to see if he would unravel in real time. Anneke, his wife, had long ceased trying to interpret his scribbled formulas. She left notes instead. There’s mould in the kitchen. You forgot bin day. Stop trying to prove God exists and answer your phone. When she left the house now, it was with the door closed carefully—like a final paragraph sealed with an ellipsis. But Karel still believed in his ritual. Not the divine kind—he had spent too long dismantling the scaffolding of God to be seduced by its silhouette—but the academic kind: dimly lit offices, sighing theatrically at student emails, filing rejections by tone. His workspace was not a desk. It was a shrine to stubbornness.

One morning, while reorganising his folder on divine emergence models (Version 17c), a subject line caught his eye:

BERLIN. EDITORS’ WORKSHOP. INNOVATION. METRICS. INVITE ONLY.

He read it three times. Then he printed it—on actual paper, of course—and placed it beneath a brass clip with the seriousness of a signed treaty.

Dear Professor Mulder,

We are pleased to invite you to an exclusive workshop for distinguished editors and scholars at Devour Publishing, hosted at the Ritz-Carlton Hotel, Berlin. All expenses covered, including travel, accommodation, and meals…

He made a noise usually reserved for particularly ill-conceived abstracts.

The Ritz-Carlton. Of course. Nothing said academic publishing quite like chandeliers and artisanal napkins. He could already see it: an endless parade of sleek intellectuals, all glowing screens and curated humility, discussing “innovative publishing trends” while privately wondering how to disappear from peer review forever. They would talk about metrics as if numbers were a form of truth. They would propose AI to fix the inefficiencies of human judgement—as if machines could approximate the slow venom of a disappointed reviewer.

Still—Berlin. He hadn’t been in years. Perhaps there was still pleasure to be found in hearing someone misquote Derrida in front of a cheese plate. He clicked “Reply.”

I will attend. Kindly send details.

Then, to restore his dignity, he picked up the latest draft of the paper on God, inhaled the scent of good paper, and reminded himself: One must occasionally engage with the world—if only to confirm that it is still not worth the effort.

II

Karel Mulder sat again at his desk, the morning light filtering through the curtains with all the enthusiasm of a disapproving librarian. The room, once a sanctuary of thought, had taken on the air of a private exhibition entitled The Noble Decline of a Man Who Once Had Potential. The bookshelves sagged like ageing aristocrats under the weight of unread tomes. Papers formed miniature mountain ranges—testaments to decades of good intentions. And in the centre of it all sat Karel, like an astronomer who had mistaken his tax return for a constellation, glaring at an equation he no longer understood but still felt morally superior to. The trouble with equations, of course, was that they did not respond to pleading. Or charm. Or perfectly constructed conditional clauses. You could curse at them in multiple languages—and Karel had—but the numbers remained unmoved. Much like Anneke.

The silence of their house was not peaceful. It was accusatory. He had once longed for silence in the way others long for fame or sex. Now that he had it, he found it pressed against his ribs like a debt collector. A door creaked in the hallway. Then came the slow, unhurried footfalls of a woman who had once walked towards him but now only walked past him.

Anneke had once been a woman of declarations—about how life was meant to be lived, not analysed; savoured, not footnoted. Over time, her vitality had been gently strangled by Karel’s indifference. It is a strange thing to watch someone shrink inside a marriage. To see brightness dull not from trauma, but from sheer, relentless disappointment. But she was not a woman to go quietly into domestic purgatory. She appeared in the doorway, arms folded, her expression somewhere between disappointment and poise.

“Karel,” she said, voice calm, “the ivy is overtaking the fence.”

There were many ways to interpret this statement. A romantic might have heard: Please, let us fix this together. A sentimental man might have heard: I need to know you still care. Karel heard: This is another task you will ignore until it becomes a metaphor.

“Can’t it wait?” he muttered, eyes still fixed on the equation, as if sheer willpower might transform it into a revelation.

Anneke’s lips pressed together with the precision of someone mentally updating her list of regrets.

“It’s important,” she said.

“More important than this?” he snapped, gesturing vaguely at the chalkboard—as if anyone else in the house had ever mistaken his work for a divine priority. Anneke raised an eyebrow. It was a well-practised gesture, honed over decades. A single, sculpted arc of disbelief.

“More important than us? More important than living, Karel?”

He hesitated. It was, as always, a trap. To say yes would be to confirm every terrible suspicion she already harboured. To say no would require some performance of tenderness, which he did not currently have in stock. And so, like a true academic, he opted for the third—and worst—option.

“I’ll deal with it later.”

Anneke exhaled. Not the sigh of a woman disappointed, but the sigh of a woman no longer surprised. She did not slam the door. That would have indicated passion. She closed it with the elegance of punctuation. Final. Undeniable. Karel sat in the silence she left behind, staring not at the door, but at the echo. Their love, he thought bitterly, was like a perfectly constructed sentence in a badly written book: technically admirable, but entirely out of place. And then—Sophie Vermeer.

The thought came uninvited, as most dangerous thoughts do. Sophie, his former student, now a professor at MIT, where her name had become synonymous with words like pioneering, visionary, and highly cited. She had never adored him, but she had engaged him—intellectually, and occasionally with scorn. She had studied her professors the way biologists study endangered species: carefully, respectfully, and with the clear aim of rendering them obsolete. She had succeeded where Karel didn’t. It was not desire that stirred in him—not exactly. It was recognition. Sophie had made him feel, once, the way equations used to: like something unknowable, like something just out of reach.

He shifted, uncomfortable with the memory. The future, he knew now, no longer belonged to him. His eyes moved to the screen. The invitation to Berlin glowed faintly, like temptation. Sophie might be there. He reached for his coffee, took a sip, and grimaced. Cold. Of course. The kind of cold that reminded you no one had made it for you. The house, once again, was silent. The kind of silence that confirmed suspicion rather than offering relief. The ivy was overtaking the fence.

Perhaps, he thought, he should let it.

III

Nina Roth stood in her apartment above the Hudson, thirty-nine floors above the city, watching a cargo ship slide slowly past the Statue of Liberty. The apartment was made almost entirely of glass and intention. Polished concrete, monochrome furniture, a bonsai tree shaped within an inch of its life. The kind of space where nothing gathered dust, because nothing was allowed to stay long enough. She held a glass of water with the same precision she brought to everything: one-third full, no ice, no nonsense. The city below throbbed with urgency, sirens and lights weaving through the dawn like a vascular system on the verge of burnout. She liked the view. She liked the illusion that she was above it all. She did not like the email she had just received. A single line from her father:

“Do you ever miss doing real work?”

She did not reply. She never replied to these. But the question lingered, like the aftertaste of too much mint. The question had a sibling: What have you actually built? Devour Publishing was profitable. Scalable. Visionary. A market leader. These were the words her team used. Her investors. Her board. And yes, occasionally, herself. But sometimes—usually before flights—she let other words through. Sterile. Extractive. Obedient. Hollow. She moved into the kitchen, if only to move. The espresso machine blinked at her like an irritated colleague. She ignored it. Poured another third of a glass of water. The morning briefing was still open on her tablet.

“Prepare: keynote language softened re: peer-review obsolescence.”

“Berlin summit attendees: note pushback from legacy editors.”

“Consider closing with a collaborative anecdote.”

She snorted. Collaborative anecdote. As if any of this had ever been a team sport. She was flying out in two hours. Berlin again. The workshop would be what it always was: a stage, a defence, a negotiation she had already won. She would arrive, deliver, smile with the right muscles, and shake hands with people who would later claim to admire her from a safe distance. And yet, the idea of stepping once more into a room full of quietly seething academics filled her with the kind of dread she reserved for dental surgery and media interviews.

Nina wasn’t afraid of their judgement. She was just tired of their surprise. Her eyes drifted to the corner of the counter where, improbably, a single envelope lay—posted, not emailed. She hadn’t opened it. It had arrived from Oxford, handwritten, addressed to her in ink with unnecessary care. From an old colleague, maybe. Or someone still trying to rescue the concept of dignity. She hadn’t thrown it away. That annoyed her most. A tremor of something rose in her—restlessness, maybe. Or its cousin, regret. She silenced it with the swipe of a finger. The time zone math told her it was already afternoon in Berlin. She checked her phone: her driver would arrive in twenty minutes. She moved back to the window, sipped her water.

Outside, the world moved on with or without permission. The cargo ship had disappeared, replaced by a tugboat that looked almost cheerful. Inside, Nina Roth turned toward her suitcase—grey, wheeled, inevitable. She zipped it closed, as though locking something in.

IV

The car met her on the tarmac. Not her idea, but protocol. The driver wore gloves—the kind that suggested the car did not belong to him. He smiled too much. She returned the gesture with a corporate nod, just warm enough to signal civility, just cold enough to end the conversation. Berlin appeared at the window like a shrug. Graffiti peeled from the walls in elegant decay. Buildings leaned against each other like friends who’d been drunk since the Cold War. There was no polished veneer here, no curated skyline. Just concrete, rebellion, and bad typography with suspicious confidence.

She didn’t like it. It was too cool. Too layered. Too unwilling to explain itself. Cities like this didn’t want to be reformed—they wanted to be survived. The hotel, at least, behaved. A glint of international capitalism in the midst of cracked pavement and anarchist stickers. Its glass façade reflected none of its surroundings, which seemed right. It looked like it had been helicoptered in from somewhere less opinionated. Inside: silence, scented air, discreet wealth. A concierge who knew her name before she said it. Nina Roth checked in without fanfare.

As she entered the elevator, a young man in a conference lanyard attempted a half-smile. She didn’t return it. Not because she was rude, but because she couldn’t afford to become a type—approachable, mentorable, soft on the inside. Her reflection in the mirrored elevator doors was exactly as she intended: poised, expensive, unavailable. She closed the door to her suite, took off her heels, and opened her tablet. The future, she reminded herself, does not need your permission. It just needs you not to blink.

VII

The taxi smelled of warm vinyl, political disappointment, and too much cologne. The driver spoke in English, the cheerful kind that implies a long-standing grudge against tourists. Karel nodded politely, said nothing. He was too busy watching the city pass by. Berlin. He had not been here in years. The city had grown rougher, stranger, more itself. Spray paint climbed every available surface. Posters flapped on lampposts—raves, protests, queer theory lectures with questionable punctuation. It was a city that didn’t tidy itself up for visitors. Karel wondered why he approved.

The buildings had the look of places that remembered too much and forgave nothing. They weren’t proud. They were still standing. That, in itself, felt honest. They passed a courtyard bar where someone was already playing techno at 3 p.m., and Karel almost smiled. This, he thought, was what the future should sound like. Indifferent. Joyless. Too loud for branding. The hotel came into view. Glass. Chrome. Designed by someone who used the word “wellness” as a verb. It did not belong in Berlin. It belonged in every other city pretending to be Berlin.

Karel stepped out of the taxi and paid in cash, to the driver’s visible confusion. His suitcase was older than some of the guests. He wore his cardigan like a protest and carried a briefcase full of paper, which made him feel both righteous and irrelevant.

Inside, the air changed. Subtle perfume. Soft jazz. The scent of suppressed complaint. He approached the front desk. A young woman greeted him with the kind of brightness that had been focus-grouped into oblivion.

“Professor Mulder?” she said, eyes darting to her screen.

“Welcome. You’re just in time for the opening panel.”

He adjusted his spectacles.

“Wonderful,” he said, with the measured enthusiasm of a man asked to applaud a spreadsheet.

As she handed him his key card—his name spelled correctly, for once—he noticed a woman striding across the lobby. Tall. Blonde. Tailored. She didn’t look around. She didn’t have to. Karel saw how the air made room for her. He didn’t recognise her. But he knew the silhouette. A corporate evangelist, he thought. AI in the bloodstream. The kind of person who’d replace a reviewer with a dashboard and call it mercy. He didn’t need her name to know what she believed. Karel took his room key. Walked toward the elevator. The carpet was too soft. The music was trying too hard. Upstairs, someone opened a laptop. Downstairs, Karel paused and muttered to no one in particular:

“And so begins the funeral of discernment.”

VIII

The day of the editor’s workshop, the air hummed low, a murmur of thoughts rising and falling, half-born and stillborn in equal measure, faint as a breath over coffee grown stale. The chairs creaked faintly, cheap wood bowing to bodies packed too tight, elbows grazing elbows, a hush over the room that felt less like anticipation and more like dread.

Karel Mulder arrived precisely on time, which was to say ten minutes too late to secure a comfortable chair but ten minutes too early to have missed the opening formalities. He took in the room with the bleak assessment of a man who had spent too many years attending academic conferences. The lighting was bright enough to induce existential despair but not quite bright enough to read without eye strain. A few attendees had already begun their subtle, strategic exits—the classic trick of stepping out to take an ‘important call’ that would last precisely as long as the least interesting presentation. But the first thing Karel noticed was the banner. It hung across the conference hall, bold and unrepentant, with the self-assured arrogance of a totalitarian slogan:

DEVOUR ACADEMIC SOLUTIONS: FOR A FRICTIONLESS FUTURE

Underneath, a group of young professionals stood behind a sleek white booth, distributing glossy pamphlets and branded USB sticks, as though they were missionaries distributing the New Testament in a particularly godless province. A screen flickered to life, playing a promotional video. A soothing voice, the kind typically used to advertise luxury sedatives, cooed:

“In today’s fast-paced academic world, knowledge must be efficient, scalable, and seamlessly integrated. Devour Academic Solutions is leading the way in AI-enhanced publishing workflows, transforming traditional academia into a frictionless ecosystem of productivity and innovation.”

Karel watched in mute horror as animated figures of scholars—represented as sleek, faceless humanoids—submitted papers with the click of a button. Moments later, AI-generated comments appeared:

“Your research is innovative. Please add 17 more citations.”

“Your abstract is clear. Please add 250 more words.”

“Your argument is sound. But please include a different methodology.”

Karel slumped lower in his chair. He longed for the dignified monotony of rejection letters, for the days when editors at least pretended to read submissions. A blonde woman in an aggressively tailored suit stepped onto the stage, introducing herself as Head of Strategic Knowledge Synergies—a title that meant precisely nothing. No one dared shuffle too loudly. All eyes fixed forward on her. Nina had arrived. Nina Roth.

She was the kind of American ambition made flesh, the kind that didn’t blink, didn’t pause, didn’t falter. Karel knew his first impression yesterday had been the right one. Nina was someone who didn’t climb the ladder—she owned it. She was amongst those who made decisions that affected thousands of people while thinking about any of them.

For a minute, Nina paused, letting the room settle, waiting until the last cough died out, until even the air seemed to still itself in anticipation.“Good Morning,” she began, her tone measured, the faintest of pauses after each syllable giving the words an unnerving clarity.

“The future of publishing has arrived. It is not a possibility, not a hypothetical—it is here, now, and it demands our attention.”

She allowed the words to linger in the air, watching the crowd with the faintest hint of a smile—not warm, not reassuring, but clinical, a scalpel’s smile. Behind her, the screen glared brightly, the title of her presentation glowing in stark white against a dark background:

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE AND THE FUTURE OF PUBLISHING

Roth moved toward it with the confidence of someone unveiling an inevitability.

“You’ve heard the rhetoric,” she continued. “The promises of AI as a tool, a partner, a supplement to human ingenuity. But let us be clear: this is not just a tool. It is a transformation. And those who fail to adapt will be left behind.” Her heels clicked against the floor as she stepped to one side, pivoting to face a different quadrant of the audience.

“Publishing as we knew it is over,” she said, each word delivered like a hammer to a nail. “The days of postmarked envelopes and dog-eared manuscripts are gone. Gone. Peer review as a labour of passion—unpaid, unrecognised—is no longer sustainable. The machine is here. And the machine is efficient.”

A murmur passed through the room, faint and uneasy, like the shifting of chairs at a funeral. Roth ignored it.

“The old system was slow. Inefficient. Flawed. It left knowledge languishing in limbo, stifled innovation, and catered to a gatekeeping elite that pretended to safeguard quality while fostering stagnation. Artificial intelligence changes all of that. Faster peer review. Cleaner workflows. Improved metrics. A revolution in how we disseminate knowledge.”

She gestured toward the screen, where a series of statistics now appeared, bold and unignorable:

97% of manuscripts processed through automated systems.

Peer-review turnaround reduced by 63%.

Journal profits up 200% since AI implementation.

“This,” Roth said, her voice carrying a note of triumph, “is the future we are building. Not tomorrow. But today.”

She paused again. Her gaze moved once more across the faces before her, assessing them with an almost predatory precision.

“And let me assure you,” she said, leaning slightly forward, her voice dropping into something more intimate, more cutting, “those who embrace this future will thrive. And those who resist? Well, history has little patience for the obsolete.”

She stepped back, her heels clicking once again, and clasped her hands in front of her. The room remained silent. In the back row, Karel shifted. His mustard coloured cardigan was buttoned high, his collar slightly askew. He sat as if cast from stone, his spectacles glinting faintly in the glow of the screen, his moustache twitching with the restless energy of an untold story. The words on the screen glared back at him, foreign and familiar all at once. Then came the provocation.

“Remember the days,” Nina said suddenly, her voice slicing through the quiet, “when manuscripts were sent by post? I bet no one still does that—anyone?”

A ripple. Chuckles. Unease. And then—his hand. Deliberate. Solitary. Karel Mulder.

“I post manuscripts,” he said.

Each word was weighted like a stone placed in a shallow stream. His voice rolled slow, Lowland-heavy.

“And I post back the reviews. Always have. I do not trust the machines. Nor the clouds.”

“Paper does not forget.”

Not reverence. Not agreement. Something stranger. Like the room had been briefly reminded it had a spine. Karel lowered his hand, feeling the gaze of his colleagues settle on him like dust on an unread manuscript. Perhaps he was a relic. Perhaps he was just right.

Ah, the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society! he thought. Established in 1665, obsolete by 1666—and yet it endured. Not because it was efficient. But because it believed in ink, and the right to take up space in margins.

Roth recovered first.

“Well,” she said, a brittle smile assembled like a hasty thesis, “I suppose some traditions die hard. But imagine how much easier it would be—with AI.”

Karel’s hand fell. His mind was already elsewhere. The clang of the postbox. The scent of ink. A margin marked by a stranger’s pen. The thread of meaning passed not through code, but care.

“And let’s not ignore the global shift,” Roth went on. “There are entire businesses built on paper-milling—authorship for hire. With AI, we can stamp that out.”

Her words settled like ash. Karel didn’t flinch. She hadn’t disproved his worldview. She had optimised it.

“AI doesn’t get tired,” she added. “It doesn’t miss deadlines. It doesn’t even require… compensation.”

The word hit him like a shard of glass. Seventeen years. He had paid for the stamps. And now the machines were coming for that, too. Life for Karel was mathematics. Not the clean, numerical kind that fits tidily on grant applications, but the unprovable sort—full of imaginary numbers and impossible limits. The kind of mathematics that ached. His devotion had always been less about answers than about order. Equations gave him what the world would not: the illusion of symmetry, the comfort of balance, the possibility that something—anything—might resolve. It wasn’t that he believed everything could be measured. It was that he feared what couldn’t. Now, sitting in a room pulsing with buzzwords and market-tested certainty, he felt the fragile elegance of his life’s logic collapse in slow motion. He stared at the screen. The phrase transformational workflow ecosystems blinked in a corner. He imagined scribbling it onto his blackboard, just to see if it would bleed.

IX

The coffee was weak. The pastries were weaker. And the mood, in the aftermath of Roth’s keynote, had the delicate tension of a piano wire strung between adversaries: one note away from music, or murder. Karel stood awkwardly near the biscuits, eyeing a Danish that appeared to be both stale and gluten-free—a theological contradiction, if ever there was one. No one spoke to him, though they glanced. Academics were good at glancing. Glances were peer review, in miniature. He lifted a recycled paper cup, turned it gently in his hand, and watched the steam spiral upwards, as if trying to escape the conversation that wasn’t yet happening. “Still believe paper doesn’t forget?”

Karel didn’t turn immediately. He knew the voice. It had the cadence of certainty carved from a spreadsheet. Roth stood beside him, sipping her coffee like it had wronged her personally. Her eyes did not seek his. They were fixed ahead, on the nametag of a departing PhD student who nearly dropped his plate upon seeing them side by side. Karel took a breath.

“I believe in memory,” he said. “Which is not the same as a database.”

“Spoken like a man who hasn’t had to de-identify 200 submissions for GDPR compliance,” she said, a little too quickly. Then quieter, more to herself: “Memory is convenient. Until it isn’t.”

A beat. Her posture remained perfect, but something in her jaw twitched—a microscopic betrayal. Karel risked a glance.

“Do you ever worry,” he said carefully, “that you’re building something people will be grateful to forget?”

Roth let the silence sit. Then she tilted her head, just slightly.

“I worry we’re already forgotten,” she said. “That we’re just ghosts arguing over workflows while the world burns.”

It was the sort of sentence neither of them had any right to say—but both of them knew to be true. Karel nodded, more solemnly than she expected.

“I thought you didn’t believe in ghosts.”

“I don’t,” Roth replied. “But I do believe in editors.”

She turned to leave then, sharp as punctuation, heels clicking against the tile with the assurance of a woman who regretted nothing but maybe—just maybe—suspected she should. Karel remained by the coffee. The cup in his hand had cooled. The Danish still looked like a lie. And yet, something in the air had shifted—not softened, not resolved—but cracked, like a page torn just enough to remind you it could be burned.

X

The sun had slunk below the Berlin skyline with the air of an exhausted hostess finally rid of her guests. The city twinkled in the distance, an expanse of light and shadow, sharp yet indifferent, much like Karel Mulder’s marriage. He stood at the edge of the rooftop pool of his unreasonably modern hotel, half-submerged in warm water, contemplating the sheer absurdity of everything. The view was magnificent, or so he supposed. He had once been capable of finding meaning in such things—in the careful arrangements of constellations, in the poetry of a well-balanced equation, even in the subtlety of an elegant footnote. But tonight, the spectacle of Berlin seemed as ornamental as the academic discussions he had endured all day. The workshop had been exactly as he expected: a gathering of people who mistook their own verbosity for insight, trading intellectual barbs like children with expensive toys. Publishing was, as ever, dying. The future was, as ever, digital. And Karel, as ever, was meant to care.

But it was Anneke who finally broke through.

His phone vibrated on the table, cutting through the illusion of solitude like a dull knife. He let it buzz for a moment, regarding it with the same suspicion one reserves for a bill that one does not wish to pay. Then, with a sigh as deep as an existential crisis, he picked it up.

“Yes?”

There was silence, the kind of silence that carries meaning. Not the comfortable silence of long familiarity, nor the polite silence of good breeding, but the heavy silence of a woman trying very hard not to say something she might regret.

“Karel,” Anneke’s voice was frayed at the edges, as though it had been pulled too tightly, too often.

“The pipe in the basement burst. The water is everywhere. I don’t know how to stop it.”

Karel closed his eyes. Of course it was the pipe. Or rather, of course, it wasn’t the pipe.

“Call a plumber,” he said, already weary of the conversation, as if fatigue could act as a shield. “You know what to do.”

Another silence. He could hear her breathing on the line, the rhythm of someone deciding whether or not to say what they truly meant.

“It’s not just the pipe, Karel,” she said finally, her voice smaller now. “It’s the house. It’s everything. It’s… us. I don’t know where we fit anymore. I feel like I’m trying to hold everything together, but I don’t even know why. And I don’t know how much longer I can keep pretending that everything’s fine.”

Karel exhaled slowly. It was a strange thing to stand in a rooftop pool of a hotel in Berlin while your wife admitted she was drowning. There was something profoundly ironic about it, something almost mathematical. He had spent his life calculating certainties, mapping the movements of celestial bodies with precision, tracing patterns in the universe that had endured for millennia. And yet here, at the centre of his own life, there was no equation that could make sense of the entropy between them. Anneke continued, the words unspooling now, desperate to be said before she lost the courage to say them.

“Can you even hear me? Or are you again just lost in your work?”

The words were barbed, and worse, they were accurate. Karel opened his eyes and gazed at the city. From up here, everything looked orderly. The lights blinked in polite synchronization, the streets below pulsed with movement, all of it appearing to follow some invisible choreography. But of course, that was a lie. Down below, people were colliding, breaking, losing things, losing each other.

“I’m in Berlin, Anneke,” he said. “I can’t help you with this right now.”

“It’s not about the house, Karel,” she whispered. “It’s about me. About us. About who we even are anymore. It feels meaningless. Like we’re just… waiting for something to happen, but nothing ever does.”

Karel ran a hand through his damp hair, his stomach tightening with the kind of guilt he had learned to ignore. He had spent years, decades, avoiding this conversation, avoiding the slow unraveling of something that once felt like permanence. But the truth was, he no longer knew what they had been holding onto. Was it marriage? Habit? The sheer force of expectation? He thought of Anneke in the house, her feet cold against the flooded basement floor, standing among the wreckage, speaking of things they had both tried very hard not to acknowledge. He thought of the ivy she had warned him about, overtaking the fence, its roots creeping into places they did not belong.

“I’m sorry, Anneke,” he said, and for once, it wasn’t just a polite exit from the conversation. “I can’t fix this from here. I’ll be back in a few days. We’ll talk then.”

A long silence.

“And until then?” she asked, though they both knew the answer. There was no until then. Just waiting. She sighed—softly, but with the weight of every conversation they hadn’t had. Then the line went dead. Karel stared at the phone for a long time before placing it back on the table. He stepped back into the pool, letting the warm water close around him, but the illusion of comfort was gone. He closed his eyes and leaned back, floating, letting the water carry him. The pipe had broken. The house was flooding. Perhaps it always had been.

XI

The dinner that evening was less of a meal and more of an endurance test in human vanity. The table stretched out before them like an overlong dissertation, adorned with flickering candlelight that cast appropriately dramatic shadows over the assembled egos. Here sat the finest minds in academic publishing—or, at the very least, the most persistent survivors of its bureaucracy. Karel Mulder, seated near the end, regarded his plate of lamb with the detachment of a man considering whether it was truly worth engaging with. His fork hovered in mid-air, less an instrument of dining than a weapon of quiet protest against the conversation that surrounded him.

At the head of the table, in full imperial splendour, sat Professor Reginald Farnsworth-Smythe. A relic of a time when scholars wore waistcoats unironically and considered the telephone an intrusion upon the sanctity of intellectual thought. He held forth like a man issuing decrees rather than engaging in discourse. His voice, polished to the brittle perfection of an old-school BBC broadcast, rang out over the table.

“The trouble with publishing these days,” he announced, pausing to swirl his wine with the theatrical precision of a stage actor preparing for his monologue, “is that it has ceased to be about knowledge. It is now a numbers game. Publish or perish. And perish we shall if these infernal algorithms continue their reign of terror.”

A murmur of agreement rippled down the table, the kind of murmur that suggested deep intellectual engagement but was, in reality, the polite hum of digestion. Karel, for his part, did not respond. He simply adjusted his moustache, a gesture that, in academic circles, could be interpreted as a sign of silent rebellion.

Professor Farnsworth-Smythe continued, his voice now swelling with righteous indignation. “It’s a deluge! And half of it comes from China, of course. Quantity over quality. The whole business is drowning in mediocrity!”

“And now,” he went on, “the latest insult: artificial intelligence. Machines!” He spat the word as though it had personally wronged him. “Devour Academic Systems believes that a programme can replace us! As if an algorithm could comprehend the sweat and toil, the sheer humanity behind every equation, every painstaking footnote—”

A younger voice sliced through the fug of wine and grievance.

“And yet,” the man said, leaning forward with the air of someone about to commit a delicious act of social sabotage, “it is not machines replacing us, but rather humans doing the replacing. Editors unpaid, peer reviewers exploited, Devour raking in billions. AI is not the real villain. We are. Or rather, those of us who keep propping up this wretched system.”

The table stiffened. Karel glanced toward the speaker—a sharp-eyed young editor who had clearly not yet learned the art of professional despair. He regarded Karel briefly, as though expecting him to issue a grand declaration in solidarity. Farnsworth-Smythe scoffed, dismissing the remark with a wave of his hand, as though brushing away an unworthy manuscript.

“Nonsense. The human touch will always prevail. We are the gatekeepers! The arbiters of knowledge!”

“Gatekeepers?” The younger man raised an eyebrow. “What gates are we keeping when authors are being bought and sold in parts of the world? When Devour monetises even the review process? The system is a racket, and we’re the ones holding it up.”

The conversation twisted from there, spiralling into a labyrinthine debate, punctuated by self-congratulation, righteous fury, and the occasional dramatic sip of wine. The token women editors at the table, present more as a nod to diversity than as actual participants, exchanged glances of quiet amusement, their silence far more eloquent than the verbal chaos unfolding around them. And then, with the timing of a man who knew exactly when to drop a bomb into an already burning building, the Portuguese editor cleared his throat.

“I must confess,” he murmured, his accent curling around the words like a well-aged Douro, “our flagship journal is… how you say… leaving.”

The table froze.

“Leaving?” Farnsworth-Smythe repeated, his chin jutting forward like an outraged vicar. “Sim,” the Portuguese editor said, swirling his wine with the slow satisfaction of a man who enjoyed such moments far too much.

“We are… how you say… sick of the Association striking all our Devour revenue.”

A collective gasp—not quite loud enough to be theatrical, but certainly scandalised—spread through the table. Somewhere in the background, a waiter coughed discreetly.

“But… it’s their flagship journal,” someone finally managed.

“Ah, sim,” the Portuguese nodded. “Was.”

He shrugged, the gesture of a man who had seen entire empires rise and fall and had simply adjusted his subscription preferences accordingly. Farnsworth-Smythe clutched his wine glass as though reconsidering its use as a weapon. Karel, meanwhile, carved another piece of lamb and chewed with deliberate slowness. It was, in its way, a beautiful moment.

Later that evening, Karel found himself in the dim glow of a bar, surrounded by a ragtag assortment of editors and disgruntled academics. “This cannot stand!” thundered Klaus-Hermann Schneider, a physicist whose moustache alone carried the weight of three revolutions. “Devour Publishing has stolen the soul of academia and replaced it with spreadsheets!”

“Careful, Klaus,” said Aoife Keane, a literary scholar whose tongue was sharper than most reviewers’ rejections. “You’ll scare the waitstaff.”

“They should be scared!” Klaus-Hermann boomed. “We all should be scared! Continuous publication? Continuous humiliation! We are not editors anymore; we are unpaid data processors!”

Murmurs of agreement rumbled through the group. Across the table, Elena Moreno, a sociologist with a gift for puncturing illusions, nodded. “Open Access should have democratised knowledge. Instead, it’s turned into a pay-to-play system. And we’re the ones keeping it afloat—for free.”

“Exactly!” Klaus-Hermann pounded the table. “Tonight, comrades, we draft a manifesto!”

Aoife raised an eyebrow. “A manifesto? What are we calling ourselves—The True Fellowship of the Peer Review? TFPR in good publishing jargon?”

The table erupted into laughter, but something quiet had shifted. Elena leaned towards Karel as the others debated fonts for the revolution. “That thing you said, earlier—about friction, about feeling your own labour through paper—”

“Yes?” Karel asked, expecting mockery.

“I think I’d forgotten that,” she said simply. “That it used to feel like something.” Aoife nodded. “You made me realise… I haven’t touched a printed thesis in years. I’ve been editing ghost documents for ghosts. At some point, I stopped noticing.”

Karel was quiet for a moment.

“Paper slows us down. That’s its greatest flaw. And its greatest gift.”

By the time the bar was closing, they had talked themselves hoarse. A few pages of the napkin manifesto had been completed—fair pay for editors, transparency in publishing fees, an end to exploitative article processing charges. Wine stains mingled with ink. It felt, if not revolutionary, at least like the beginning of something.

“Right,” said Aoife, pulling out her phone. “I’m not walking back in these heels, and I’m certainly not paying for a taxi. Let’s bleed Devour dry with their own bloody vouchers.”

Karel frowned. He had never used a ride-sharing service before, let alone on someone else’s tab. But practicality was triumphing over principle tonight. Aoife tapped at her phone with practised ease. Within minutes, a sleek black car pulled up. The group squinted at it doubtfully.

“There’s no way we’re all fitting in that,” Elena said, eyeing Klaus-Hermann’s substantial frame.

“We’ll make it work,” Klaus-Hermann declared, folding himself into the passenger seat with all the grace of a giraffe attempting yoga. Karel and Elena slid into the back, followed by Aoife, who wedged herself in last. The door shut with a muffled thud, and the car immediately felt smaller than it looked.

“Evening,” the driver said cheerfully, adjusting his mirror. He was young, with kind eyes and an accent that spoke of warmer, dustier places. “Where are we headed?”

“The Devour-funded prison block,” Elena quipped, rattling off the hotel’s name.

The driver chuckled, his smile genuine. “Ah, academics, yes? Here for the big conference?”

“Something like that,” Klaus-Hermann grunted, clutching his manifesto as though it contained the solution to all the world’s injustices. The driver navigated the Berlin streets with a practised ease. After a few minutes, he glanced at them through the rear-view mirror.

“You know, I used to be an academic.”

Karel perked up. “What field?”

“Economics,” the driver said with a faint smile. “I taught at a university in Sudan. But, well… circumstances change.”

The car fell silent. Elena was the first to speak. “That’s… heartbreaking.” The driver shrugged, his tone resigned but not bitter, “It’s life. I drive now, I send money back home, and my son is studying. Maybe he’ll have better luck.” Klaus-Hermann, uncharacteristically quiet, finally spoke. “Do you miss it?”

The driver’s eyes met his in the mirror. “Every day,” he said. “But knowledge isn’t tied to a job. I still read. I still learn.” They pulled up to the hotel. Elena murmured “Gracias.” Aoife added, “You’re more of a scholar than most people in that conference room.” Karel paused, one foot still in the car. “And paper?” he asked, softly. The driver smiled. “I write letters. Every week. They never crash.” They disappeared into the hotel lobby as conspirators in a crumbling empire.

XII

Before bedtime, Karel Mulder found himself stripped not just of his cardigan and trousers, but of the last shreds of his dignity, sitting naked and alone in the hotel’s sauna. The heat pressed down upon him like an overdue monograph, each bead of sweat rolling down his skin a physical manifestation of his mounting existential crisis.

The wooden panels exhaled the weary sigh of decades of academic suffering, steeped in pine, perspiration, and the quiet regrets of scholars who had once believed their work mattered. His moustache, usually a proud bastion of defiance, drooped pathetically under the oppressive humidity. He leaned back against the slats, wincing as the wood stuck to his damp skin. How had it come to this?

It was not the pomposity of Farnsworth-Smythe that haunted him—after all, there would always be men who mistook their own obsolescence for wisdom. It was not even Roth and her sterile, surgically efficient vision of the future, where academia was reduced to a frictionless conveyor belt of knowledge production, void of humanity. No, what troubled him most was the revelation.

They get paid.

The words had landed like an anvil in his chest. Two younger editors—insufferable in their casual ease—had stood by the coffee station, unaware that their conversation had detonated a bomb inside his skull. “Fifty grand a year just to chase reviewers.” “And it’s all remote. No more conferences unless we want to go. They even pay for travel. It’s cake.” Karel had almost dropped his coffee.

Seventeen unpaid years. Seventeen years of licking stamps, of deciphering the ancient runes of reviewer feedback, of writing polite-yet-pleading emails to academics who could not be bothered to respond. Seventeen years of believing in the nobility of his work, in the quiet integrity of the system. He had been a fool. Now, in the suffocating heat of the sauna, the enormity of his naïveté bore down on him. His chest tightened. His fists clenched against his thighs. He had spent his life in service to a machine that did not even acknowledge his existence.

The door creaked open, and a broad, bald man lumbered in, his body glistening like a wet boulder. He sat heavily on the opposite bench, sighing with the satisfaction of a man untroubled by the weight of his own thoughts.

“You look troubled,” the man observed, wiping his face with a towel.

Karel hesitated, then burst forth, his words tumbling over one another like an overdue grant proposal. “Seventeen years! For nothing! They laugh at me! I pay for the stamps! Do you understand? I post manuscripts by hand!”

The man regarded him with the blank neutrality of a bureaucrat listening to a faculty grievance. “Maybe you should start charging,” he said simply, then stood, slinging the towel over his shoulder as he lumbered back out.

Karel sat in stunned silence, the man’s casual remark ricocheting inside his skull. Charge? Could he? Could he pivot so drastically, abandon the moral high ground he had clung to with such fervour? Would charging not reduce him to the level of the very system he despised? The coals hissed softly in the corner, sending another wave of heat rolling over him. He closed his eyes.

What stung him too wasn’t Roth’s arrogance or Farnsworth-Smythe’s bluster—it was Elena and Aoife. He had dismissed them at first, these sharp-eyed women with their biting wit and unrelenting critiques. But over the course of the workshop, he had found himself seeking them out. Their words—quick, cutting, but oddly kind—had forced him to examine things he had spent years avoiding.

“It’s a system that eats its own young,” Elena had said, her voice steady but fierce. “The wealthy institutions thrive, while the rest of us scramble to keep up. And the labour? Always unpaid, always invisible.”

Karel had bristled at first—how dare she speak in sweeping generalisations? But later, when they had crossed paths in the hallway, she had stopped him. “I’m sorry if that came off too strong,” she had said. “It’s just… it’s frustrating, isn’t it? Knowing we give so much to a system that barely acknowledges we exist.” Karel had nodded, and to his own surprise, had meant it. Then there was Aoife. Over lunch, he had been silent for too long, staring absently at his plate.

“Don’t tell me you’re still thinking about Roth’s presentation,” she had teased. “If we let people like her live in our heads rent-free, we might as well start paying for their coffee too.” He had laughed despite himself. Now, in the sauna, their words mixed with the steam, cutting through his usual defences. He realised with a jolt that he had begun to admire them—these women he would have once dismissed as too young, too brash, too irreverent. Maybe they weren’t so different after all.

He stood, the heat finally unbearable, and wrapped his towel around himself with a kind of defiance. He would think more on this later. For now, he needed to write. He needed to do something. Perhaps tomorrow, he would seek out Elena and Aoife. Not as adversaries, but as allies. Perhaps tomorrow, he would start asking the questions he had avoided for so long. Tonight, though, he would sit at his desk—towel-clad and determined—and begin the process of untangling the knot in his chest. He didn’t yet know what the answer would be. But the asking—that, at least, felt like a beginning.

Back in his hotel room, still wrapped in his towel like a fallen emperor, Karel paced. His notes, scattered across the desk, glowed under the desk lamp like the ruins of a once-great civilisation. “Transformative Agreements.” A euphemism for exploitation, he muttered. He swiped at the papers, as if obliterating the words might make them less insidious. Devour Academic Solutions. The name lingered in his mind like a malignancy. Devour was more than a company—it was a mission statement. It had consumed academic publishing, gutted it, repackaged it, and sold it back at a premium.

The so-called Open Access revolution? A scam. A system that had promised to democratise knowledge had been reduced to a transactional farce, where researchers in underfunded institutions bore the brunt of astronomical publishing fees. And AI? The creeping, insidious tendrils of automation had begun wrapping themselves around his sacred domain. Pre-written peer reviews, automated editorial processes—what burden were these corporations trying to ease? The burden of thinking? The burden of care?

Karel stopped pacing. His reflection in the dark window startled him. He looked… wild. His hair disheveled, his moustache unkempt, his towel slipping dangerously low. And then, suddenly, he turned, pointing a dramatic finger at the empty room.

“You! Yes, you! Sitting in your ergonomic chairs, sipping your matcha lattes, talking about efficiency and scalability!”

His voice rose, bouncing off the beige walls.

“You are not stewards of knowledge; you are predators! Peddlers of human intellect, packaged and sold as a commodity!”

He paused, savoring the imagined collective gasp of his unseen audience.

“Predators in Armani,” he added softly, pleased with the phrasing.

He exhaled. The rage was still there. But beneath it, something new, dangerous. Tomorrow he would do something about it. Tonight, though, he would sit in his towel, pour himself a glass of overpriced minibar whiskey, and plot his revenge the only way he knew how: methodically, carefully, and on paper.

XIII

Nina Roth stood barefoot on the cold tile floor of her hotel suite, staring out at Berlin. The city flickered. Graffiti clung to every surface. Nothing apologised for its history. Even the streets seemed to mutter. She sipped at a glass of wine that had gone warm and sour.

The keynote had landed. The photos had been taken. The metrics were already climbing. She had delivered. Every word, every pause, calibrated. There had even been applause. But something small and unfamiliar had lodged beneath her ribs. She had not eaten at the dinner. She had laughed at all the right cues, nodded sagely at the Portuguese editor’s announcement, and made a brisk, strategic exit. Now she was alone in the suite Devour had booked. Glass walls, blackout curtains, water that lit up blue when poured. The kind of room where no one stayed long enough to shed anything personal.

On the desk lay a branded tote bag, still zipped. On the bed, her keynote note cards fanned out like tarot. She had half a mind to shuffle them and read her future.

She moved to the mirror and looked at herself. The suit still looked sharp, but her skin didn’t quite match it. There were fine lines now at her mouth, soft grooves at her temples. Her hair, always scraped back into defiance, hung limp from the humidity. Her eyes looked off. She remembered what the man had said. The one in the cardigan. “Paper does not forget.” It was absurd. Sentimental. And it had rattled her. Not because he was right, but because a part of her, some small dusty corner, still wanted him to be. She sat down on the edge of the bed, the mattress dipping beneath a weight she hadn’t realised she was carrying. Her hands trembled as she reached for her phone. A message glared up at her: “Well played today. Strategic pivot to anti-fraud talking points was a masterstroke.”

She turned the phone over. There had been a time she used to write in notebooks. Her first job, her first journal. Messy handwriting, black ink smudged by the corner of her hand. It had felt like thinking. She hadn’t written anything longhand in years. She pulled a sheet of hotel stationery from the drawer and picked up the hotel pen.

For a long time she stared at the page. Then she wrote in small script:

“If I stopped running, would there be anything left of me that wasn’t velocity?”

She stared at the sentence. Then crossed it out. Wrote beneath it: “Paper does not forget.” She folded the page in half, placed it beneath her glass, and turned away from the window. She didn’t bother brushing her teeth. Just kicked off her shoes and lay down, fully dressed. Her keynote cards fluttered off the bed and onto the floor. She let them. And for the first time in weeks, she didn’t set an alarm.

VII

The workshop room hummed with the low murmur of anticipation, the kind of polite tension that always preceded the unveiling of another grand illusion. Redefining Value in the Publishing Ecosystem, the slide announced in sleek, emotionless font. The title was so impressively vague that it could have meant anything from the systematic eradication of editors to a new line of monogrammed tote bags.

Karel sat near the back, as was his habit, his eyes sharp beneath furrowed brows. The previous evening’s indignation had not faded but rather settled. It was a fury no longer raw but refined, honed like the edge of a well-worn letter opener, the kind used to slice through rejection letters with exquisite precision.

The speaker—a man who had never needed to lick a stamp in his life—strode to the podium with the kind of confidence only afforded to those who had never known the burden of real labour. He was polished, slick in the way only a corporate man could be, the sort of person who spoke of optimisation while thousands toiled in obscurity beneath the weight of his vision.

“Efficiency,” he began, his voice as smooth as his tailored suit. “Scalability. AI-enhanced workflows. This is the future of publishing.”

Karel’s stomach turned. The buzzwords poured forth, light and airy, like the empty calories of an academic soufflé.

“At Devour, we’ve revolutionised the industry. Open Access is no longer a dream; it’s a reality.”

The speaker paused, smiling, as if expecting applause. Karel did not applaud. He did, however, feel the sudden and urgent need to throw something. A reality for whom? he wanted to ask. For those who can afford the article processing charges? For those in institutions so wealthy that the cost of publishing is a line item lost among gala dinners and corporate sponsorships? He pictured the researchers in underfunded institutions, scraping together grants, cutting into their own stipends, desperate for the privilege of being published, while Devour’s executives sipped champagne and talked of democratisation.

The speaker was not finished.

“And with our latest acquisition,” he continued, “we’re integrating AI to streamline peer review. Our proprietary algorithm, Peer Review-as-a-Service™, guarantees faster turnaround times and higher reviewer satisfaction.”

Karel let out a derisive snort before he could stop himself. Faster? Yes. Accurate? Debatable. More Satisfaction? Never. He imagined again the faceless algorithm spewing out formulaic feedback: “The methodology is sound but could use further elaboration.” Stamp. Next. “This paper is promising but requires more citations.” Stamp. Next.“We appreciate your submission but regret to inform you that” Stamp. Next. And all of it, neatly packaged, wrapped in the illusion of impartiality, and sold at an obscene profit.

Then, just as the audience was settling into the usual rhythm of passive complicity, something unexpected happened. The screen flickered. A live feed, unfiltered, uncurated, appeared before them. A Microsoft Teams chat. Internal. Real-time.

“Ugh, these editors are so old-fashioned.”

“Bet half of them still use fax machines.”

“Did you see the guy yesterday who still mails manuscripts? Literal dinosaur lol.”

“Imagine working for free for 17 years. Can’t relate.”

Gasps rippled through the room. The speaker, his slick veneer of professionalism cracking, fumbled with the controls. A frantic moderator attempted to remove the feed. But it was too late. The words hung in the air like the smell of burnt coffee, bitter, acrid, and impossible to ignore.

Karel’s face burned. His moustache bristled with the full weight of his indignation. He had been called many things in his life—anachronistic, certainly; impractical, perhaps—but dinosaur? And by the very people whose salaries were paid with the bones of the labour he had so willingly, so stupidly, given away? He rose.

“Excuse me,”he said, his voice cutting through the silence, “but am I to understand that this is how the so-called leaders of academic publishing view us? As relics? As dinosaurs?”

All eyes turned to Karel. The speaker, frozen at the podium, looked as if he would very much like to dissolve into the floor.

“Seventeen years!” Karel continued, his voice rising. “Seventeen years of unpaid labour! Seventeen years of licking stamps, deciphering the illegible scrawls of anonymous reviewers, mailing manuscripts by hand, because I believed, foolishly, in the sanctity of this profession!”

He paused, scanning the room.

“And yet here you stand, laughing at us, exploiting us, while you rake in billions from the fruits of our labour!?”

The applause started tentatively, hesitant at first, as if the audience needed permission to rebel. But then it grew, gathering momentum, swelling into something undeniable. A small triumph, yes. But a triumph nonetheless. The speaker’s face had turned a shade of white normally reserved for undercooked fish. With a hurried nod to the moderator, he stepped away from the podium, vanishing from sight. The session was abruptly called to an end. Karel lingered as the room emptied. The fight was far from over. But for the first time in years, he had felt something that had long been absent. Something like power.

VIII

The hotel bar was the kind of place that believed itself sophisticated but was, in truth, merely expensive. Low lighting, brass fixtures, the soft murmur of intellectual fatigue mixed with overpriced gin. The bartender stirred drinks with the solemnity of a man who had seen too much. The chairs were designed for discomfort in the name of elegance, and the entire atmosphere reeked of polished surfaces and curated restraint, the kind that suggested all excess must be paid for in existential despair. It was, in short, the precise opposite of the mood at Karel’s table.

He sat slumped in a slick velvet chair, his cardigan unbuttoned, his tie half-undone, the last of his whiskey swirling like an afterthought in his glass. Across from him, Aoife Keane lounged with the insouciance of someone who had already decided she was drinking on the company’s tab, while Elena Moreno methodically crushed a lemon peel between her fingers, as if it represented the publishing industry itself.

“Well,” Aoife exhaled, stretching her legs beneath the table, “that was spectacular.”

Karel let out a sigh. “I assume you mean my public execution at the hands of Devour Academic Solutions.”

“No, no,” she said breezily. “That was cathartic. I meant the bit where their private team messages accidentally appeared on the conference screen. That was art.”

Elena smirked. “It was,” she admitted. “Although I do wonder if they’re currently trying to delete the evidence or if they’ve already started drafting an apology email so insipid that it will somehow include the phrase We regret any offense caused while standing by our commitment to innovation.”

Karel scowled. “They were laughing at me. Dinosaur lol, wasn’t it?”

Aoife raised an eyebrow. “Well, Karel, you still send manuscripts by post.”

“I told you. I believe in the sanctity of paper.”

“Of course you do.” She took a sip of her wine. “But that’s not really what’s bothering you, is it?”

Karel hesitated, swirling the amber liquid in his glass.

“It’s not,” Elena cut in, leaning forward, unrelenting. “It’s the fact that you gave them seventeen years of free labour, and they mocked you for it.”

Karel inhaled slowly. That was it. That was the unbearable weight pressing against his chest. It wasn’t merely the insult, it was the truth behind it. The truth that he had been a fool. That he had convinced himself his unpaid labour was a service, a duty, when in fact it had simply been exploited. His entire professional identity had been built on the belief that dignity lay in the work itself, not in the compensation. But perhaps that, too, had been a lie.

Aoife watched him carefully. “It’s a sickening thing,” she said, “realising that the house you thought you were building was never yours at all. That you were just laying bricks for someone else.”

The words hit him harder than expected. Because wasn’t that exactly what Anneke had been trying to tell him all those years? “I need you to see me.” And he had dismissed her. Not cruelly, not consciously. But he had dismissed her all the same, offering half-answers, distracted nods, treating her pain as a minor disturbance in the greater scheme of things. Because his work was important. Because his routine mattered. Because he had built a world for himself in which duty came before everything else. And yet, wasn’t that precisely what these corporate executives had done to him? They had smiled, nodded, praised his diligence, right up until the moment they made it clear that he had been irrelevant all along. He had, in the end, been devoured.

Elena sighed and leaned back. “Look, Karel, I’m not saying you need to start worshipping AI, but I am saying that clinging to paper and stamps doesn’t make you immune to the system. It just means you suffer more while they profit regardless.”

He rubbed a hand over his face. “So what are you suggesting?”

She exchanged a look with Aoife.

“We fight back,” Aoife said simply.

Karel let out a weary laugh. “And how do you propose we do that? Stage a coup? Form an underground resistance? Distribute samizdat-style pamphlets on the dangers of corporate monopolisation in publishing?”

Aoife grinned. “Now you’re thinking like a revolutionary.”

Elena smirked. “It’s not as dramatic as you make it sound. We call them out. We demand transparency. We make noise. And,” she leaned in slightly, her expression serious, “we stop giving them our time for free.”

The words settled heavily between them. A crackling sound broke in. A breath of static. The bar’s retro sound system exhaled like an overworked postdoc. And then a voice, sultry and defiant, soaked in whiskey and war stories. “I’m not a good girl, I’m a bad woman… Aoife’s ears perked up. A slow grin spread across her face, something mischievous unfurling beneath her usual acerbic wit.

“Oh, now this,” she murmured, “this is a sign.”

Karel frowned. “A sign of what?”

“A sign,” Aoife said, rising from her stool, “that it’s time for a bit of cultural disruption.”

Before either of them could protest, she had sauntered to the front of the bar, where a battered microphone stood, unused but waiting, much like Karel’s manuscript on God. Elena groaned. “Oh no. She’s doing it.” Aoife turned, her glass raised, her dark Irish eyes gleaming with mischief.

“For the unpaid! For the overworked! For the undercited!”

And then she began to sing. A slow ripple of recognition, approval, and shared exhaustion moved through the room. A woman in a sociology department fleeceraised her drink in solidarity. A philosophy professor, who had spent the last twenty minutes in silent despair, began to sway slightly.

“I drink all night, I stay out late, I make mistakes, but they’re mine to make…”

Someone in the back cheered. Karel sighed, rubbing his temples. “I had suspected as much.” As Aoife delivered the final line, she threw her arms wide, as if to embrace the entire absurdity of the publishing industry. And for a moment, the weight of unpaid labour, of endless peer reviews, of citation metrics and the creeping horror of AI, all of it lifted. Karel clinked his glass against hers. It was, perhaps, the first moment in years that he felt part of something worth believing in.

The third round of drinks had been poured, the bar was growing louder, and Aoife, still basking in the triumph of her impromptu performance, had taken it upon herself to flirt outrageously with a bewildered but clearly interested political theorist two stools over.

Elena, swirling the last of her wine, gave Karel a knowing look. “You’re not really coming to the champagne reception, are you?”

Karel feigned outrage, placing a dramatic hand on his chest.

“Elena, please,” he said, “I have every intention of attending and partaking in the hollow, soulless rituals of the academic elite.”

“Hmm.” Elena took a sip, unimpressed.

Aoife turned back to them, suddenly attentive. “Wait, what’s happening? Karel, darling, are you defecting?”

Karel sighed.

“I will join you later,” he said. “But first, I need air.”

Aoife squinted at him, then at Elena. “This is what men of a certain age say when they are about to fall into an existential crisis in the rain.”

“That’s ridiculous,” Karel said, rising.

“You’re going to stare at a puddle and question everything, aren’t you?”

“I said I’d join you later.”

Elena smirked. “Be careful, Mulder. Too much fresh air and you might start rethinking your entire career.”

He gave them a final nod, shrugged on his coat, and stepped out into the Berlin night. The air outside hit him like a shock of reality—cool, damp, alive. The warmth of the bar, the rattle of glass, the low hum of drunken theorizing, all of it faded. He could have stayed. He could have indulged in another round of camaraderie, another knowing toast to their collective disillusionment. But disillusionment, Karel thought, was best experienced alone.

The champagne reception would still be there when he returned. The clinking of glasses, the self-congratulatory murmurs, the gentle nodding of heads in feigned agreement. All of it would wait. He pulled his cardigan tighter, his indignation bubbling beneath it like a kettle just shy of boiling. His mind drifted back to the Portuguese editor. A man who had watched entire publishing empires rise and fall and had simply adjusted his subscription preferences accordingly. The one who had shrugged, unbothered, as he announced that his journal had defected, as if leaving a sinking ship was not a scandal but a basic survival instinct. Karel envied him, in a way.

There was no great moral struggle in him, no restless need to justify the system or change it from within. He had seen the game for what it was and played accordingly. Perhaps I have been too noble, Karel thought. Perhaps I have mistaken servitude for integrity. He had spent too many years believing in a thing that did not believe in him back. And the Portuguese editor, in his quiet, detached way, had moved on without grief. Was that wisdom? Or just mildly elegant cynicism? And then there was Anneke. A different kind of injustice. A different kind of betrayal. Not by an institution, but by time itself. By the slow, creeping erosion of what had once been bright and certain.

“I need you to see me.” She had said it plainly. And he had heard her. But had he listened? He stopped at a street corner, watching the headlights of passing cars paint fleeting constellations on the wet pavement. He had spent his life predicting patterns. But what use was a theory of the universe if he could not even map the slow unraveling of his own marriage? He had thought that certainty was a kind of love, that dedication to one’s work was an act of fidelity. But Anneke had seen it differently. To her, it had been a quiet abandonment. He had been faithful to his work. But not to her.

He wandered toward a narrow passageway, where a section of the old Berlin Wall still stood, half-covered in rain-darkened graffiti. A remnant of division, left in place as a warning, a monument to folly. What was knowledge but another kind of wall, another way to separate oneself from what truly mattered?

He thought of all the papers he had edited, all the monographs that had passed through his hands, each one carrying some carefully argued theory, some urgent plea for relevance. And yet, when the world truly changed, when walls fell and nations collapsed and histories rewrote themselves overnight, what had academia done? Published special issues about it. He smirked. It was not knowledge itself that was futile. It was the belief that it had ever been more than an echo.

Karel exhaled.

Tomorrow, there would be another session. Another speech to be made, another panel to endure, another polite disagreement that changed nothing at all. But tonight, he would walk. The wind moved through the streets, carrying the sound of distant music, the rustling of leaves, the faint murmur of lives being lived beyond academia. For tonight, he was just a man in a city that did not need him.

IX

The streets were alive with the usual urban symphony. And yet Karel walked as though through fog, his mind replaying the indignities of the day: Devour’s gloating, Anneke’s pouring out over a broken pipe, the relentless parade of statistics, the smug panelist declaring AI would soon write better peer reviews than humans, “more objective and far quicker.” The audience had nodded solemnly, and he had wanted to scream. When the flicker of candlelight caught his eye, it felt almost like a sign. A window framed by red velvet curtains glowed invitingly, the soft light promising something both decadent and absurd. Above the door hung a sign: Fortune Teller Extraordinaire—Your Future Awaits. Beneath it, in smaller, scrawled letters: With Jerome, the Spiritual Dummy.

He hesitated on the threshold. A ventriloquist dummy? Really? But the weight of the day had loosened his usual reserve, and he pushed open the door, stepping into a haze of clove cigarettes and spilt Riesling. Inside, the bar was a peculiar temple to excess. Red velvet draped every surface, and candles sputtered in tarnished brass holders, their wax pooling like tiny, molten sculptures. The bartender, a man who looked as though he’d crawled out of a Kafka novel, sold single cigarettes with one hand and swigged from a bottle of Riesling with the other. Karel slipped into a chair at the back, his cardigan still buttoned up like a shield against whatever madness lay ahead.

The crowd was no less surreal. A young Berliner with lipstick smudged to the point of artistic intent lounged near the stage, mentioning her OnlyFans account to anyone within earshot. A Danish filmmaker scribbled furiously into a notebook, pausing only to sip an Aperol Spritz with studied nonchalance. Across the room, a Polish architect, newly returned from Scotland, gestured wildly as she proclaimed the virtues of affordable housing, her accent a lyrical blend of Kraków and Edinburgh.

Karel clutched the programme he hadn’t thought to discard, feeling as though he had stumbled into a dream he didn’t quite understand. And then, with a flourish of emerald silk, the show began. The fortune teller, a striking woman with piercing brown eyes, swept onto the stage, her ventriloquist dummy cradled in one arm. It was grotesque and grinning, its painted moustache disturbingly reminiscent of the editor’s own.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” she began, her voice smooth and commanding, “tonight you will not find answers, only better questions.”

The dummy, Jerome, clacked his wooden jaw. “And maybe some answers if you’re lucky…or rich.”

The audience chuckled, a low murmur punctuated by the hiss of cigarettes. Karel tried to remain aloof, but he couldn’t help being drawn in. When a nervous audience member asked about love, Jerome replied, “Stop texting your ex at midnight, and you might find some.”

Karel’s moustache twitched, betraying his amusement. Yet as the act went on, he felt an uncomfortable resonance with the dummy. The way Jerome spoke sharp truths while being entirely controlled by another hand. It struck a nerve. Wasn’t he, too, just a dummy in the grand machine of academic publishing? His voice swallowed, his efforts invisible, his labour exploited to feed the profits of Devour and its ilk? As if sensing his unease, Jerome’s painted eyes seemed to turn toward him. The dummy’s grin widened.

“You, sir,” Jerome rasped. “What’s your question?”

Karel froze. The room seemed to blur, the smoke and candlelight closing in. Finally, he cleared his throat. “Am I… am I living my life, or am I just a ventriloquist dummy?”

The room fell silent, the weight of his words hanging heavy in the air. Jerome tilted his head, as though contemplating the profundity of the question.

“Deep,” the dummy said at last. “Maybe stop licking stamps, eh?”

The room erupted into laughter, a wave of sound that rolled through the smoky haze. Karel felt heat rise to his face, but it wasn’t humiliation. It was release. He laughed too. It wasn’t a loud laugh, nor a long one, but it was real. The kind of laugh that shakes something loose inside you. As the show ended, he lingered, watching the strange assortment of characters file out. The Berliner flashed him a conspiratorial smile. The architect pressed a card into his hand, whispering, “If you ever want to talk about housing, find me.” The filmmaker muttered, “Good metaphor,” before disappearing into the night. He sat alone for a moment, the melted wax pooling on the table, the faint echo of Jerome’s voice still rattling in his ears. Perhaps he wasn’t just a dummy after all. Perhaps he could be more. Perhaps, even, there was hope for publishing. Not in Devour’s ruthless efficiency, but in the spirit of true openness.

Karel thought of open access done right: platforms run not for profit, but for progress. Journals where knowledge wasn’t locked behind paywalls, where labour was recognised, where editors weren’t reduced to unpaid ghosts. He pictured a future where collaboration replaced exploitation, where transparency was more than a buzzword, and where authors weren’t just products to be packaged and sold.

The bartender approached, bottle in hand. “Another drink?”

He smiled faintly. “No, thank you,” he said, standing and buttoning his cardigan with a newfound sense of purpose. “I think I’ve had enough for tonight.” And as he stepped back into the Berlin night, the air thick with promise and cigarette smoke, he felt lighter somehow. Tomorrow, there would be more smug panellists, more talk of metrics and AI.

X

The streets stretched before Karel Mulder, slick with rain, their puddles glinting like spilled mercury under the amber glow of the streetlamps. The city had shed its urgency, emptied of its daytime quarrels and negotiations. Somewhere, his colleagues were celebrating their victories—real or imagined—over clinking champagne glasses, exchanging business cards and vague promises of collaboration, already half-forgetting the grand ideas that had seemed so urgent mere hours ago. Karel had no such desire for company. He walked without a destination, his coat pulled tight against the damp air, his mind a carousel of unfinished thoughts. He had not won, not truly. But for the first time in years, he had said something aloud that had needed to be said. And that, perhaps, was something.

And then, as he turned onto a narrow, rain-darkened street, he saw Nina Roth.

She walked slowly, hands tucked into the pockets of her coat, shoulders set as straight as ever but lacking their usual sharpened precision. She no longer looked like a panther about to strike, but rather a woman walking off the day, unwinding herself, untangling the tightly coiled spring of efficiency she had wound so carefully each morning. Her immaculate charcoal-grey coat, which all week had given her the air of a woman immune to wrinkles, literal or metaphorical, now hung looser on her frame, the rain darkening the fabric. The armour had slipped.

Karel hesitated. He could turn back. He could duck into an alley, pretend he hadn’t seen her, avoid the risk of whatever conversation might follow. But something about her, the unguarded way she moved, the quiet solitude of her presence, compelled him to step forward. His shoes clicked against the cobblestones, and at the sound, Nina turned.

“Ah,” she said, her voice steady, unreadable. “Herr Mulder.”

“Frau Roth,” he replied with a nod.

They stood for a moment in a hush, neither moving to close the distance nor to walk away. Rain pattered softly around them, collecting in the cracks of the pavement, washing the world clean in ways that were only ever temporary.

Karel shifted. “Walking off the workshop?”

Her lips curved, just slightly. It wasn’t the knowing, calculating smile she wore so well. This was smaller, softer.

“Something like that,” she said. “You?”

“I find it helps,” he said. “A walk, I mean. Clears the head.”

She considered this for a moment, then gestured faintly down the street. “Would you mind the company? Or do you prefer to walk alone?”

“I don’t mind,” he said.

Their steps were slightly out of sync at first but found a rhythm quickly, falling into an easy, companionable silence. The air thick with the scent of wet stone and woodsmoke. Karel had spent his life in the company of words, and yet now, as they walked side by side, he found himself grateful for the lack of them. Finally, it was Nina who spoke.

“You know,” she said, her voice low, thoughtful, “I don’t think I’ve ever really been to Berlin before.”

Karel glanced at her, surprised. “No?”

She shook her head. “I never seem to go anywhere except for work.”

He nodded, something about the quiet honesty of her admission catching him off guard.

“And you?” she asked.

“I don’t travel much,” he admitted. “I prefer my routines.” He paused, glancing at her. “But I suppose that wouldn’t suit someone like you.”

A small laugh. “Someone like me,” she echoed. “And what do you think that is?”

Karel hesitated, choosing his words carefully. “Efficient,” he said finally. “Focused.”

Her smile turned wry. “That’s one way to put it.”

She stopped walking, her gaze lifting to the windows of an apartment across the street, their glow painting faint halos against the rain.

“Do you know what I do when I’m not working?” she asked.