This blog post is part of the Seminar Reconceptualizing Warfare and Its Experience, April 10, 2025, funded by the WARFUN project.

I love the Norse mythology. I really do, and the idea is just fucking great that when we die, we go to the Great Hall [of Odin] to drink and fight, right? I think that’s beautiful. But at the end of the day, I do believe that I’m more Christian than in favour of the old Norse gods.

– PV2 Eriksen,[1] OIR, Al Asad Airbase, Iraq

To Valhalla and Armadillo: Public awakenings to pleasures of war

Mazar-e-Sharif, Afghanistan, September 2010. “You are the hunters. You are the predators. Taleban is the prey. To Valhalla! To Valhalla! To Valhalla!”.[2] Thus sounded the battle cry led by the commander of the Norwegian Telemark Battalion’s 4th Mechanized Infantry Company (Coy). Standing on top of an infantry fighting vehicle, Company Commander Rune Wenneberg was addressing his soldiers rallying around him. They resolutely responded by raising their rifles against the sky in time with their shouting of the old war cry: “Hurrah! Hurrah! Hurrah!”. This rousing of fighting spirits was recorded on video, published by Dagbladet, shared in social media, and stirred a public outcry. What was going on? Did the deployed Norwegians actually take part in acts of combat, and did they on top of that do so as the revival of blood-thirsty Viking warriors?

Earlier in the same year, in May 2010, the Danish war documentary Armadillo had its first night. The film, directed by Janus Metz, portrays the war in Afghanistan from the perspectives of young Danes deployed to Helmand with the Guard Hussar Regiment’s 1st Mechanized Infantry Company. Foreshadowing the moral indignation at the To Valhalla-video in Norway, a heated debate followed in the Danish public in the wake of Armadillo’s opening. What was going on? Did Danish soldiers actually engage and kill so-called ‘insurgents’, and did they on top of that do so with pleasure? To judge from the scenes depicting Danish troops high on the ecstasy of combat, high on the delights of reenacting acts of killing and telling tales from the battlefield, and high on the joys of bravado and comradeship, Armadillo exposes an inconvenient truth about war, an ethically disturbing taboo: war is fun, war is pleasurable. To be sure, war is death and destruction, pain and suffering. Yet, there is more to war than misery. There is more to war than a price to be paid in terms of human costs. Indeed, there might also be a prize to be won in terms of happiness (Pedersen 2017b), be that hedonic in the sense of feeling good, or eudemonic in the sense of doing good (Walker & Kavedžija 2015). Either way, happiness, it seems, might be a warm gun.

Pride in (Lost) Glory: Reconfigurations of war experience

However ethically disquieting it might be, a variety of pleasures appears to be fundamental to war experiences across time and place. Exploring the role of fun, and of pleasure more broadly speaking, an emerging field of research within the humanities and the social sciences has particularly within recent years gained momentum and reconfigured the experience of war (Bourke 1999; Lyng 2005; Gordon 2006; Harari 2008; Neitzel & Welzer 2012; Basham 2015; Brænder 2016; Pedersen 2017a, 2019; Saramifar 2018, 2019; Welland 2018; Achilli 2025; De Lauri et al 2025; Hamer 2025; Jelušić 2025; Johais 2025a, 2025b; Maringira 2025; Mogstad 2025; Rastrilla & Donofrio 2025; Sciarrino 2025; Tomforde 2025), not least thanks to Antonio De Lauri’s WARFUN project. Contributing to this reconfiguration, the present paper examines a pleasure of war that has not, it seems, gained much attention so far, namely the pride in glory.

Based on fieldwork with Danish combat soldiers deployed to Al Asad Airbase, Iraq, in support of Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR), I ethnographically and anthropologically investigate the emotion of pride in relation to the reputation and conceived glory not only of Danish troops who served in combat roles in the Danish Helmand campaign in Afghanistan (2006-2014), but also, and above all, of their construed ancestors: Danish Viking warriors in the days of old. In this context, the aim of this piece is to direct our attention to the emotion of pride as an important factor in fighting for who ‘we’ are and for what ‘we’ believe in.

Analytically, I attend to different aspects of pride: its agential and non-agential dimensions as well as its connections to social status and audience. I sketch out what at this stage of my work constitutes a tentative analysis; an analysis demonstrating that the focus on pride in the present context opens a window not so much into individual pride as into group-based pride. I show that the study of pride offers insight into happiness, hedonic as eudemonic. That is, into soldierly pleasures of feeling good about doing good in terms of feeling proud of one’s achievements and of one’s being and becoming, including one’s belonging to and standing of one’s group, be that one’s unit or one’s nation. By the same token, I argue that soldierly pride in glory is intimately tied not only to patriotism/nationalism within the ranks of the armed forces, but also to esprit-de-corps, morale, will to fight, and thus, ultimately, fighting power.

On the varieties of pride: A very short conceptual note

Theoretically, this piece draws upon the work of Alba Montes Sánchez and Allesandro Salice (2023) in conceptualising pride as an emotion along three different lines. First, approaching pride as an emotion of self-appraisal, we can, with Antti Kauppinen (2019), distinguish between two kinds of pride: ‘agential’ and ‘non-agential’. When feeling agential pride, one feels good about one’s achievements, such as defeating one’s enemy in a firefight. By contrast, non-agential pride refers to feeling good about one’s relatively steady qualities, such as one’s identities, character traits, abilities, or values. For instance, one’s warriorhood, one’s perseverance, one’s combat skills, or one’s warrior ethos. Second, emphasising the social dimension of pride, we can direct our attention to pride as an emotion evaluating one’s individual standing within a group (Sánchez & Salice 2023). Following Thomas J. Scheff (1990) we can differentiate between ‘true pride’ and ‘false pride’. The former ‘signals a secure social bond and generates open and respectful interactions’ (Sánchez & Salice 2023: 36), while the former ‘involves a self-aggrandising attitude and motivates behaviours that seek to obtain or signal one’s superiority over others, including contempt and aggression’ (ibid.: 37). Third, turning to ‘hetero-induced pride’, that is, to our capacity to feel proud of others, such as one’s company or one’s forefathers, we bring collective identifications and group-based pride to the fore. In doing so, this variant of pride indicates that ‘how significant others fare in the world can have a deep impact on our own self-appraisals’ (Sánchez & Salice 2023: 31, emphasis in original).

Some words on context: Vikingification of Danish armed forces

The groups of Danish soldiers that Armadillo followed up close belonged to Vidar Coy, as the then newly formed mechanized infantry company was called and thus named after one of the Norse gods, namely the son of Odin associated with vengeance. All the same, unlike To Valhalla, Armadillo did not dramatically confront its audience with the military’s use of the Nordic Viking past. Yet, one has not to be much familiar with the Danish armed forces in general, or with Denmark’s participation in international military operations in particular, to take notice of the fact that Danish troops, as with the case of their Norwegian counterparts (Dyvik 2016), frequently take pride in and visibly associate themselves with the Vikings and their Norse gods: names, call-signs and insignia of several Danish units and camps draw inspiration from the Viking Age and Norse mythology (Frisk 2017; Pedersen 2017b). Moreover, Viking-inspired imagery, runes, and ornaments decorate online memorials to Danish soldiers killed in the ‘Global War on Terror’ (Stage & Knudsen 2012) and tend to be among the most popular motifs of the tattoos and jewellery adorning the living bodies of Danish soldiers and veterans (Frisk 2017; Pedersen 2017b; see also Grarup 2013).

The use of Nordic Viking past in the Danish armed forces seems to have increased coincidently with the growing ‘warriorisation’ of Danish military professions in the heyday of the Danish Helmand campaign (Pedersen 2021a). However, militant/militarised invocations of Viking warriors and Norse gods are nothing new. Indeed, it forms part of the Viking revival, which has been ongoing since the Romantic era (Wawn 2000; Adriansen 2003; Dyvik 2016), and the use of Viking-imageries within the ranks of the Danish Army can be traced back to the Danish-Norwegian involvement in the Napoleon Wars (Glenthøj 2012). Fast forward to the Second World War: Danish Nazis were back then frequently drawing upon Norse mythology to evoke the might and glory of the Danish nation (Adriansen 2003). For instance, Mjolnir, the hammer of Thor, the Norse god of thunder and war, adorned the black standard of the Danish Nazi youth (ibid.). Here, we could also recall the rune-inspired insignia of Nazi Germany’s Schutzstaffel (SS), not to mention the fact that the 5th SS Panzer Division was named “Wiking” – presumably because of its many Nordic volunteers. On this background, it can hardly surprise that the contemporary far-right in the Nordics and elsewhere tend to be fond of Vikings and Norse gods. Think, for example, of the anti-immigrant group Soldiers of Odin, which patrolled the streets of several Nordic towns in response to Europe’s ‘migrant crisis’ in 2015.

To be sure, historically as contemporarily, the use of the Nordic Viking past in Denmark is by no means associated with right-wing nationalists only. For instance, during the Second World War, Tyr, the Norse god of war, became the symbol of the Danish youth that was ready to sacrifice itself in the resistance against the Nazi occupation of Denmark (Adriansen 2003). Today, Vikings have long been a national brand in Denmark, as elsewhere, and are eagerly used in marketing. Indeed, Vikings and Norse gods have become common in Denmark to judge from the number of museum exhibitions related to the Viking Age, and from the number of Viking fairs and Viking fight clubs and reenactments, let alone from the continuous popularity of Peter Madsen’s Valhalla comic series (1979-2009). Add to this the more or less dark heroification implied by the growing global Hollywoodification of Vikings and Norse gods, which has been stimulated within recent years by the TV series Vikings (2013) and Vikings: Valhalla (2022) as well as by Marvel’s film Thor (2011) and several sequels.

A few more words on context: A blaze of glory

Empirically, this piece is based on fieldwork with the 1st Mechanized Infantry Coy, 2nd Armored Infantry Battalion, 1st Brigade, Jutland Dragoon Regiment. The approx. 130-strong Company was formed in 2011 and named ‘Viking’. The Company is based at the Dragoon Barracks in Holstebro, Mid-Jutland, where the Company’s insignia, a cartoonish twin-headed axe, adorns the Company’s quarters. In 2012, the Company deployed to its first international military operation: the NATO-led ISAF mission in the Afghan Helmand province.

In comparison, Viking Coy’s older sister company, the 4th Armored Infantry Coy, known as Four of Diamonds, deployed to Helmand in 2008. Back then, the tours of duty were combat missions. However, by the time that Viking Coy arrived in theater, the main emphasis of the mission had shifted to training of Afghan security forces and to transferring the security responsibility to the very same Afghan forces. Viking Coy was subjected to a British-led battle group and based at Main Operating Base (MOB) Price in Helmand’s Nahri Saraj District. The Company suffered no fatalities and had “just” a few seriously ‘wounded in action’. It was likewise in the case of Four of Diamonds, and both companies thus made “just” a small contribution to the statistics that no one wants to be part of: Denmark’s military participation in the US-led war in Afghanistan (2002-2021) resulted in the loss of 44 lives of deployed Danish men and women, more than two hundred physical injuries, and a still growing number of mental and emotional war wounds.[3]

The number of Danish war deaths and physical war injuries are by far concentrated in the time and place of the Danish Helmand campaign. This campaign became defining not only for the Danish military efforts in Afghanistan, but arguably for the Danish national self-image too, and perhaps even also for Danish national pride. At least this seems to be the case to judge from three related and often invoked narratives among observers in the Danish public as well as among Danish soldiers and veterans: first, the Helmand campaign involved the Danish Army’s fiercest fighting since the Schleswig War of 1864, thereby reviving Denmark as a warring nation. Second, the number of Danish casualties during the campaign meant that Denmark was the coalition partner in ISAF with the highest number of soldiers ‘killed in action’ per capita. Third, the campaign implied that Denmark, as a small European nation, was punching above its weight.

***

In 2018 and 2019, Four of Diamonds and Viking Coy, respectively, joined the fight against Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) when the two companies deployed to Anbar in support of the US-led OIR mission. Both companies were organized into Company Training Teams and Guardian Angels. Both companies were tasked with the training of Iraqi security forces and were not permitted ‘outside the wire’ of Al Asad Airbase. As with the case of the prior seven Danish OIR rotation teams, Four of Diamonds and Viking Coy were based at the US-operated Camp Havoc located at the heart of the Iraqi-controlled airbase.

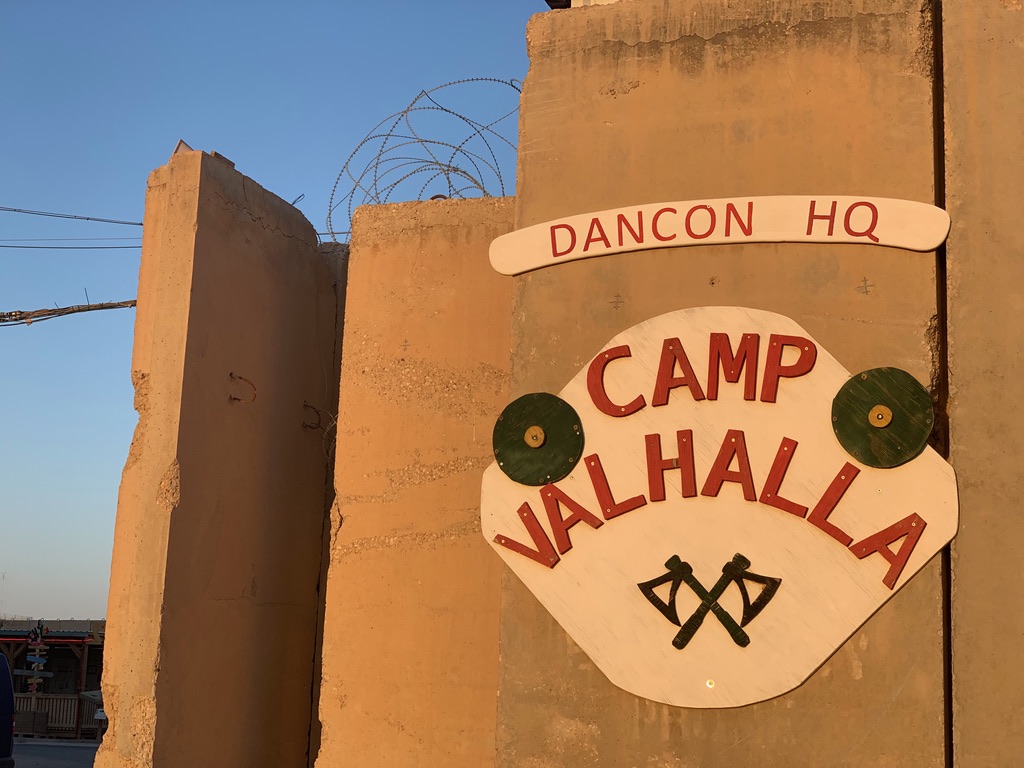

Apart from infantry, the Danish rotation teams were compounded of several other units, including, among others, staff, military intelligence, and camp engineers. The Danes were based at a number of small camps scattered across Havoc. Among these, as it was the case with the Norwegian Camp Midgard, a few took their names after Norse mythology: Valhalla (staff centre and quarters), Asgard (CCT and GA command centres), and Utgard (GA quarters). Add to this, the blast wall mural of the Vikingified, Danish national folklore hero, Holger the Dane, guarding the entrance to the work areas of the Danish radar detachment and camp engineers.

Viking pride: A tentative analysis

In this section I outline the rough contours of my preliminary analysis. Reflecting the linguistic, material, bodily, and actional presence of Viking (Coy) pride among my interlocutors, the section is organized into four subsections: emplotments, entrenchments, embodiments, and enactments:

Emplotments

I’m proud of being a Viking. The old ancestors – there was bloody well not so much bullshit going on. Not according to the history books anyway … I’m of course proud of the fact that Viking Coy was formed in the old Afghanistan. So, we serve amid that old history of the really old boys who deployed and who took part in fierce battles back then. So, I’m also taking much pride in being in Viking [Coy] because of that. Knowing that their legacy is conveyed, and that those boys have not been away in vain. You’ve not just left and switched off the light when they returned home. So, I’m taking much pride in that as well.

– GA, PV2 Eriksen

We have this history of being feared in most parts of the world. Not that we should be feared in the whole world again, but it’s just that it forms such a big part of our history … Denmark is a small nation. We don’t have that many muscles to flex. So, I just think it’s awesome that we have something as epic as Norse mythology and the entire history of the Vikings.

– CTT, LCpl Björnsson

Comparing Eriksen’s and Björnsson’s accounts, the narrator integrates himself into the Viking plot, as a member of Viking Coy and/or as a member of the Danish nation. Eriksen gives voice to a non-agential, yet group-based pride: on the one hand, in – as Eriksen perceives it – the Vikings’ no-bullshit-way of being, and, on the other hand, in Eriksen’s sense of belonging to Viking Coy. As such, Eriksen’s pride seems to be ‘true’ in Scheff’s (1990) sense by way of signalling a strong social bond to both Vikings and Viking Coy. However, Eriksen does also appear to feel agential pride not only in the accomplishments of Viking Coy on the Afghan battlefields, but also in the present day’s safeguarding of the Company’s legacy. Pride, it seems, offers a window not only into a sense of company-based esprit-de-corps, but also into a cultivation of the Company’s track record and warrior culture.

By comparison, Björnsson takes non-agential, yet hetero-induced, pride in the epic dimensions of the Viking Age, all the while he also seems to feel agential pride in the horror caused by Vikings around the world. By implication, Björnsson’s pride tends to come across as one harbouring nationalistic undertones, or, in Scheff’s (1990) terminology, as a ‘false pride’, an aggressive haughtiness. In any event, in the case of both Eriksen and Björnsson, the feeling of pride, it seems, involves a pleasurable sense of masculinised self-enlargement, a sense of existential potency (Pedersen 2021b), a morale booster, that is.

Entrenchments

You show that this here, this is us [by virtue of the Vikingified camp names and insignia], and this is the way we would like to be seen, and this is something we’re proud of … So, I think it’s totally awesome that we leave our mark [on Al Asad], so people know who we are, and what we stand for … Although we no longer plunder and rape.

– GA, PFC Aagaard

I think the first time I saw that things were named after one thing or another [in Norse mythology], I thought, ‘come on’. To be honest, I think it was a bit dumb. But then again, it’s fine. Things must have a name … I just think that people who are not Danes have soon had enough of us staging ourselves so much all the time in relation to something that happened 1,400 years ago … I acknowledge that we have this [Viking] history, and that’s also great. Yet, it’s also a bit unfortunate that this is really our only source of pride.

– CTT, Sgt Steffensen

Aagaard’s and Steffensen’s accounts contrast with one another. Aagaard identifies with a collective ‘we’, be that Viking Coy or the Danish nation, and seems to feel proud of who ‘we’ are, namely once were Viking warriors – at least as Aagaard perceives it. In any event, Aagaard appears to find pleasure in ‘being-for-others’ (Sartre 1943/2018; Sánchez & Salice 2023), in being an object of perception for Denmark’s coalition partners at Camp Havoc: Norway, Germany, Poland, and the USA. By comparison, Steffensen, most of all, it seems, feel embarrassed, even alienated, from the Danish Viking theme at Al Asad. Indeed, the invocation of the Danish Viking past tends to make Steffensen feel the negative counterpoint to pride, namely shame (Sánchez & Salice 2023). Thus, instead of feeling pleasure, Steffensen seems to feel ashamed not only about his and his fellow-countrymen’s being-for-others, but also about their apparent lack of prideful achievements since the Viking Age.

The use of the Danish Viking past is in other words disputed among my interlocutors. For the many like Aagaard it tends to evoke a sense of existential potency, a sense of having presence and significance in the world (Pedersen 2021b). For the few like Steffensen, on the other hand, the Vikingification of Al Asad appears to summon a sense of existential impotency, a sense of lost glory, perhaps even exposing Denmark, not as a revived waring nation, but rather as a nation with a long history of military defeats.

Embodiments

I think it’s awesome that we bring Norse mythology along [to Al Asad]. Also, because we’re Viking Coy, and we live our lives a little through that, and we carry it on in that way … The warrior is still in the Danish culture. Even though we are a small nation, we can still go out and fight against an enemy who outnumber us, or who is just as competent as we are … So, the warrior mentality it’s still there within each and all of us … It’s great that we can keep up our reputation and bring that part of Denmark into modern times.

– GA, PFC Aagaard

I must admit that I’m quite annoyed that the Norwegians [based at Camp Midgard] have our company name [as an Al Asad call sign]. We have a sense of ownership toward that name. In one sense it’s a silly thing. Yet, it would of course be fab if they decided to use another name, and we then could use it … I’ve acquired a certain pride in carrying the [Viking Coy] patch and in saying that I’m from this Company. That’s also because I’ve been here so long. I’ve been part of those things that have defined the Company. It makes me feel proud to be able to say, ‘I was there, and I was part of that’.

– CTT, Sgt Steffensen

Staying with Aagaard and Steffensen, it is interesting to note the difference in the kinds of pride they feel. Aagaard gives expression to a group-based, non-agential pride in who ‘we’ are as Viking Coy and, by implication, as Danes, namely warriors (as Aagaard sees it). Indeed, according to Aagaard, warriorhood seems to form an integral part of being Danish: all Danes have a warrior mindset, an ‘inner warrior’ so to speak. Warriorhood seems to form a kind of cultural legacy, not to say cultural DNA, which, as Aagaard perceives it, each and every Dane embodies by virtue of descending from the Vikings, and which is materialised in the Danish deeds in the Afghan battlespaces. As such, Aagaard’s pride tends, with Scheff (1990) to be a ‘false’ one because it involves a somewhat aggressive and self-aggrandising attitude with nationalistic undertones. Accordingly, this kind of pride may motivate Aagaard’s will to fight and dare him to prove what ‘kind of stuff’ he is made of.

By contrast, Steffensen’s pride seems to be more to the ‘true’ side (ibid.) in terms of indicating not only strong ties to Viking Coy, but also respectful interaction with the Company’s Norwegian counterpart despite the name/call sign controversy. Curiously, although Steffensen tends to feel ashamed of the Vikingification of Al Asad, he appears to take much individual, non-agential pride in Viking Coy’s name and patch. However, this kind of pride, it seems, is intimately tied to the fact that Steffensen is one of “the really old boys”, as PV2 Eriksen puts it above. Consequently, Steffensen feels a lot of agential pride, that is, he feels quite good about himself because of his own part in Viking Coy’s defining experiences and achievements in Afghanistan.

Now turning to SFC Berthelsen’s account below, it is not only the interwovenness of embodiment and materialisation that becomes manifest, but also the entanglement of pride and audience:

Well, I think, when the Americans look at us, then they think that we’re quite some Vikings. Because each of us is a hell of a guy because we’re not dressed in the same way as they are. In the Danish Army you’re allowed to have the kind of beard you want. We have decided that whether you’re a good or a bad soldier isn’t a question depending on whether you have a full beard. So, that’s why they envy us a bit. We’re also allowed to wear boots that fit our feet … I don’t know if that’s a part of the Vikings. I just think it’s the Danish mentality. It must work for us … But maybe we look like some daredevils because we’re not all wearing the same boots, and we have the haircuts we like to have.

– CTT, SFC Berthelsen

Berthelsen feels non-agential pride in what he describes as “the Danish mentality”, which in comparison with the American one, makes Berthelsen stand out like “a hell of a guy”. At least that is so when Berthelsen adopts the perspective, real or imagined, of the US troops at Al Asad. In that perspective, Berthelsen, it seems, finds pleasure in his and his ‘fellow-Vikings’ being-for-others, in their being as objects for perception, in their being as objects perceived as “daredevils” by virtue of their non-uniform, ‘undisciplined’, and thus hyper-masculinised warrior-like looks.

Enactments

The Vikings were all warriors. Great warriors. Big and strong warriors. And those Americans we’ve been talking to, they do also say, “Danish Vikings”, right? That’s what they call us … Even Four of Diamonds were called “Danish Vikings”. So, that’s what we’re known for, and I think it has a whole lot to do with the way in which the Danish Army performed in Iraq and Afghanistan. Although, we were only like 400 men in total, we made a huge impression by fighting as equals with the Americans and the British … We could do the same as they could, and sometimes even better.

– CTT, LCpl Björnsson

We call ourselves Vikings, but to me it has nothing to do with the proper Viking Age … As for the axe [depicted at the heart of the Viking Coy insignia] it does not historically correspond with the Viking Age. It might look more like a Medieval halberd … The Viking Age is appealing, and people think it’s awesome. So, alright, they associate us with that, and we have sometimes joked about going out raiding when we go to one place or another. But to me it has no deeper meaning.

– CTT, Sgt Steffensen

Comparing Björnsson’s and Steffensen’s accounts, the former is dead serious about the use of the Danish Viking past, while the latter portrays it as fun or even ridicules it. The former account connects the Viking theme with sensemaking, while the latter shows the connection to be close to meaningless. Björnsson seems to feel good about the fact that US troops at Al Asad are referring to Danish soldiers as “Danish Vikings”. He appears to feel a hetero-induced, non-agential pride in the Vikings as warriors and an agential pride in the achievements of the Danish Army in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. However, Björnsson’s pride tends once again to be ‘false’ (Scheff 1990) in political and military terms because of its self-aggrandising attitude with nationalistic undertones. Yet, in existential terms, Björnsson’s pride is arguably imbued with a sense of masculinised self-enlargement as well as with a sense existential potency. Steffensen, on the other hand, takes no pride in other nationals perceiving him and his fellow-countrymen as Vikings. On the contrary, Steffensen seems to feel ashamed about the lack of historical accuracy involved in the Vikingification of Viking Coy and other Danish troops. That said, Steffensen is still able to find pleasure in the use of the Danish Viking past, namely as a source of dark humour.

Concluding remarks

In this piece I have ethnographically and anthropologically explored a pleasure of war that tends not to have gained much scholarly attention, namely the soldierly pride in glory. Based on my ethnographic fieldwork with Danish combat soldiers serving in Viking Coy on a tour of duty to Al Asad Airbase, Iraq, in support of Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR), I have made a rough outline of a tentative analysis of pride in (lost) glory. In a nutshell, I have sketched out a preliminary analysis of pride as an emotion evoked by past deeds of Viking Coy in Afghanistan as well as by the use of Danish Viking past at Al Asad, be that along the lines of emplotment, entrenchment, embodiment, or enactment. Emerging from the analysis, we can see, I contend, the contours of soldierly pride as a pleasure of war, not so much in terms of warm gun happiness as in terms of we-ness happiness, be that ‘we the battle-seasoned Viking Coy’, or ‘we the Danes who once were Vikings’, that is, great warriors, as the masculinised self-enlarging (his)story goes.

References

Adriansen, I. (2003). Nationale symboler i Det Danske Rige 1830-2000. Vols. I-II. København: Museum Tusculanums Forlag.

Achilli, L. (2025). “Boko Haram’s ‘Playground’: Exploring the Role of Fun among Children Associated with Armed Groups in Nigeria.” War & Society 44(1): 95-112. DOI: 10.1080/07292473.2024.2409533

Basham, V. M. (2015). “Waiting for War: Soldiering, Temporality and the Gendered Politics of Boredom and Joy” In Military Spaces. In Emotions, Politics and War, ed. L. Åhäll and T. Gregory, 128-140. New York, NY: Routledge.

Bourke, J. (1999). An Intimate History of Killing: Face-to-face Killing in Twentieth -century Warfare. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Brænder, M. (2016). “Adrenalin Junkies: Why Soldiers Return from War Wanting More.” Armed Forces & Society 42(1): 3-25. DOI: 10.1177/0095327X15569296

De Lauri, A., Achilli, L., Jelušić, I., Johais, E. and Mogstad, H. (2025). “Introduction to the special issue: war and fun: exploring the plurality of experiences and emotional articulations of warfare and soldiering.” War & Society 44(1): 1–13. DOI: 10.1080/07292473.2024.2409532

Dyvik, S. L. (2016). “‘Valhalla rising’: Gender, Embodiment and Experience in Military Memoirs.” Security Dialogue 47(2): 133-150. DOI: 10.1177/096701061561573

Frisk, K. (2019). “Armadillo and the Viking Spirit: Military Names and National Myths in Transnational Military Interventions.” Critical Military Studies 5(1): 21-39. DOI: 10.1080/23337486.2017.1319644

Glenthøj, R. (2012). Skilsmissen: Dansk og norsk identitet før og efter 1814. Odense: University Press of Southern Denmark.

Gordon, R. J. (2006). “Oh Shucks, Here Comes UNTAG!”: Peacekeeping as Adventure in Namibia.” In Tarzan Was an Eco-Tourist and Other Tales in the Anthropology of Adventure, ed. L. A. Vivanco and R. J. Gordon, 217-234. New York, NY: Berghahn.

Grarup, J. (2013). Mærket for livet: Tatoveringer blandt Livgardens soldater. København: Gyldendal.

Hamer, P. (2025). “War Jokes and Humour in Besieged Sarajevo, Bosnia–Herzegovina from 1992 to 1995.” War & Society 44(1): 154-171. DOI: 10.1080/07292473.2024.2409536

Harari, Y. N. (2008). The Ultimate Experience: Battlefield Revelations and the Making of Modern War Culture, 1450-2000. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Jelušić, I. (2025). “Entertainment and Fun in the Service of Survival: Theatre of the People’s Liberation in the Battles of Neretva and Sutjeska.” War & Society 44(1): 14-30. DOI: 10.1080/07292473.2024.2409537

Johais, E. (2025a). “The WARFUN Taboo.” War & Society 44(1): 66-81. DOI: 10.1080/07292473.2024.2409538

—. (2025b). “Schlagfertigkeit. A Soldier Skill.” Critical Military Studies 11(3): 312-328. DOI: 10.1080/23337486.2025.2472101

Kauppinen, A. (2019). “Pride, Achievement and Purpose.” In The Moral Psychology of Pride, ed. J. A. Carter and E. C. Gordon, 169-190. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Knudsen, B. T. and Stage, C. (2013). “Online War Memorials: YouTube as a Democratic Space of Commemoration Exemplified through Video Tributes to Fallen Danish Soldiers.” Memory Studies 6(4): 418–436. DOI: 10.1177/1750698012458309

Lyng, S. (ed.) (2005). Edgework: The Sociology of Risk-taking. New York, NY: Routledge.

Maringira, G. (2025). “Wartime Soldiers, Civilian Relations: Zimbabwean Soldiers in the Democratic Republic of Congo War 1998–2002.” War & Society 44(1): 82-94. DOI: 10.1080/07292473.2024.2421640

Mogstad, H. (2025). “‘Playing War’: Norwegian Soldiers’ Experiences of Fun and Responsibility in Afghanistan.” War & Society 44(1): 46-65. DOI: 10.1080/07292473.2024.2409539

Pedersen, T. R. (2017a). “Get Real: Chasing Danish Warrior Dreams in the Afghan ‘Sandbox’.” Critical Military Studies 3(1): 7-26. DOI: 10.1080/23337486.2016.1231996

—. (2017b). Soldierly Becomings: A Grunt Ethnography on Denmark’s New ‘Warrior Generation’ (unpublished dissertation), Dept. of Anthropology, University of Copenhagen.

—. (2019). “Ambivalent Anticipations: On Soldierly Becomings in the Desert of the Real.” The Cambridge Journal of Anthropology 37(1): 77-92. DOI: 10.3167/cja.2019.370107

—. (2021a). “Facing the Warrior: An Ethnographic Montage on Post-9/11 Warriorisation of Danish Military Professions.” In Transformations of the Military Profession and Professionalism in Scandinavia, ed. A. Roelsgaard Obling and L. Victor Tillberg, 94-115. Copenhagen: The Scandinavian Journal of Military Studies Press. DOI: 10.31374/book2-e

—. (2021b). “’Democracy … 120 mm at the Time’: Mission Formations and Operational Entrapments in Post-9/11 Afghanistan.” In Military Mission Formations and Hybrid War: New Sociological Perspectives, ed. T. V. Brønd, U. Ben-Shalom and E. Ben-Ari, 141-166. New York, NY: Routledge.

Neitzel, S. and Welzer, H. (2012). Soldaten – On Fighting, Killing and Dying: The Secret Second World War Tapes of German World War POWs. London: Simon & Shuster.

Rastrilla, L. P. and Donofrio, A. (2025). “A Place for Laughs in Hell. Martínez de León’s Cartoons: Republican Humour in the Spanish Civil War.” War & Society, 44(1): 131–153. DOI: 10.1080/07292473.2024.2421645

Sánchez, A. M. and Salice, A. (2023). “Feeling Good about Myself Because of You, Because of Us”. In Emotions in Culture and Everyday Life: Conceptual, Theoretical and Empirical Explorations, ed. M. Hviid Jacobsen, 30-44. London: Routledge.

Saramifar, Y. (2018). Enchanted by the AK-47: Contingency of Body and the Weapon among Hezbollah Militants. Journal of Material Culture 23(1): 83-99. DOI: 10.1177/1359183517725099

—. (2019). “Tales of Pleasures of Violence and Combat Resilience among Iraqi Shi’i Combatants Fighting ISIS.” Ethnography 20(4): 560-576. DOI: 10.1177/1466138118781639

Sartre, J.-P. (1943/2018). Being and Nothingness: An Essay in Phenomenological Ontology. New York, NY: Routledge.

Scheff, T. J. (1990). Bloody Revenge: Emotions, Nationalism and War. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Sciarrino, B. (2025). “War as a Game: The Pleasurable and Playful Aspects of the Italian Arditi’s Military Experiences in the First World War.” War & Society 44(1): 31-45. DOI: 10.1080/07292473.2024.2409529

Tomforde, M. (2025). “Processing Violence: The Continuum between Fear, Doubt, and Joy among German Soldiers in Afghanistan.” War & Society 44(1): 113-130. DOI: 10.1080/07292473.2024.2409530

Walker, H. and Kavedžija, I. (2015). “Values of Happiness.” HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 5(3): 1–23. DOI: 10.14318/hau5.3.002

Wawn, A. (2000). The Vikings and the Victorians: Inventing the Old North in Nineteenth-Century Britain. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell & Brewer.

Welland, J. (2018). “Joy and War: Reading Pleasure in Wartime Experiences.” Review of International Studies 44(3): 438-455. DOI: 10.1017/S0260210518000050

[1] My translation.

[2] All my interlocutors go under pseudonyms to shield their identities.

[3] No official records are publically available on the numbers of casualties caused by Danish acts of combat in Afghanistan.